Our requirements for the solution

The deletion request is something that a client is not expecting to fail. There are no validations, and from a business perspective it’s an operation that should always succeed.

In order to cater for this and to solve the problems that we anticipated to face, we needed to design a solution that allows us to:

- Have the ability to restart the operation in cases of failure

- Have the ability to accommodate it running for relatively long periods of time without wasting resources

As we discussed earlier, there’s no response requested to be delivered back to the client. This is almost like a fire-and-forget situation from the client’s perspective.

Deciding for an event-driven setup

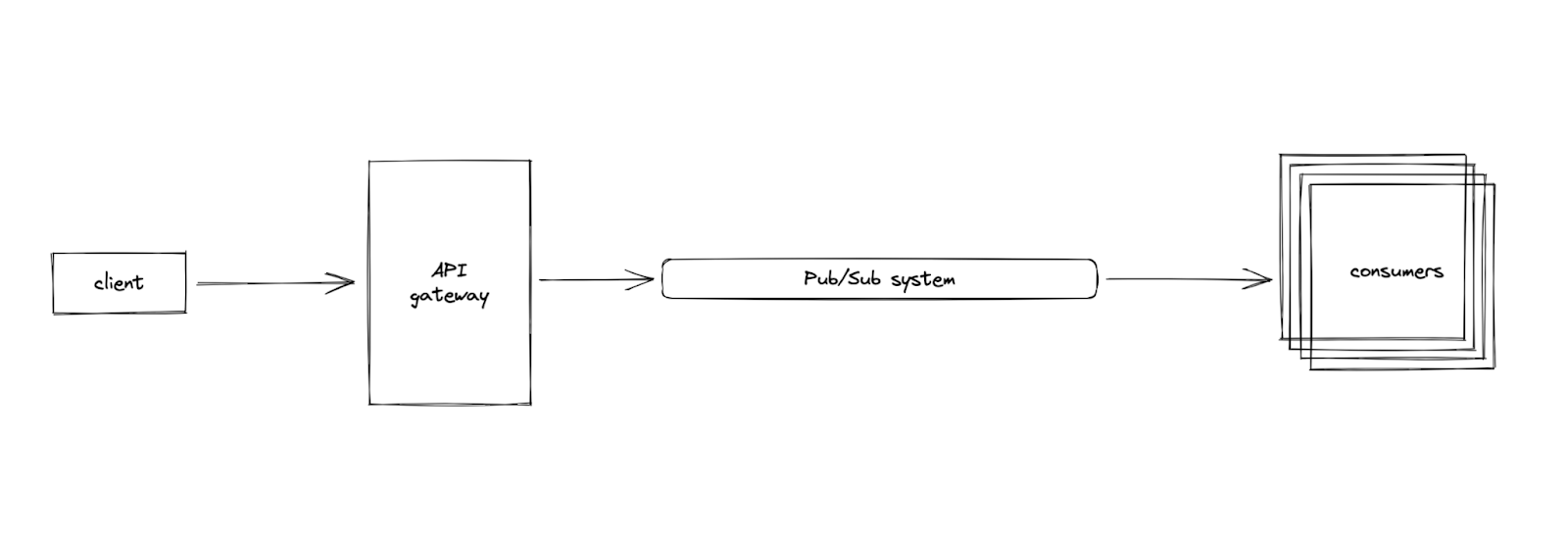

Due to its asynchronous nature, an event-driven solution looked like a good fit.

There are several benefits from this approach:

- We get retry-ability out of the box.

- The processing of the deletion is decoupled from the placement of the request. The client hits the endpoint, and an event is emitted, and the request is done. The event is then independently picked up by consumers. This also makes way for us to scale the publisher and the consumers independently.

- We get plug-and-play-ability that serves our service-oriented architecture well. The endpoint is exposed by our gateway, which doesn’t own data. Emitting an event frees the gateway from knowledge about which services need to fulfill the request, which means that we can add more services in the future without changing the logic of the endpoint.

Handling Failures

Of course, this doesn’t solve our problem out of the box. There are still some downsides that we need to take into account, including the ones imposed by introducing an event-driven system into your architecture. We host all of our instances on GCP, so we decided to use their Pub/Sub implementation.

So, what kind of failures specifically can we anticipate?

- Something goes wrong with the consumer itself (e.g. it fails to consume the event).

- Something goes wrong during the deletion, because of an issue that happens while processing which is caught.

- Something goes wrong during the deletion, because of other issues (deployment is happening, node is lost, etc.).

- Something goes wrong which we can’t catch.

Clearly, we wanted to make the solution fool proof, so we needed to address each of these issues carefully.

1. If a consumer fails to consume the event, the Pub/Sub system comes with an acknowledgement mechanism that can help with that. If one of the subscribers fails to acknowledge an event, the event will be retried. This is usually implemented in a sophisticated way using algorithms like exponential backoff so that the system doesn’t make an unnecessary number of retries.

2. If something goes wrong during the deletion because of the application logic, we can catch that and act on it. Consequently, we decided that we should keep track of deletion jobs, and give them a notion of “status” so that we can recover from failures. Therefore, if we are able to catch an application issue, we can update the status of a given job to “failed”. We will touch upon resuming such jobs later.

const deletionJobSchema = new Schema<DeletionJob>({

botId: {

type: Schema.Types.ObjectId,

ref: 'bot'

},

status: {

type: String,

enum: Object.values(DeletionJobStatus)

},

createdAt: {

type: Date,

default: Date.now

},

lastModifiedAt: {

type: Date,

default: Date.now

},

});

3. If something goes wrong during the deletion, but not because of the application logic, there’s a chance we might catch it. For example, we can catch kill signals and implement graceful shutdown logic that would allow us to mark all in-progress jobs to “failed”, before finally killing the app.

Before we touch on the fourth error scenario, let’s talk about resuming from failures. We talked about different cases where we label some jobs as “failed”, but how do we re-run these?

For that purpose, we decided to have a cronjob that runs daily, and calls an endpoint which queries for a failed job and resumes it. It’s worth noting here that the way this endpoint works is that it initiates the process of finding a job to resume, then the request is done. It doesn’t wait for the deletion process, as again this might make it prone to request timeout issues.

Now, back to our last error scenario:

4. How do we recover from failures that we were not able to catch? Meaning, if there was a deletion job that was in-progress, and something went wrong but the system was not able to label it as “failed”, how do we find out about these?

In the query where we find failed jobs (which is triggered by the cronjob), we not only look for a job which has a status set to failed, but also make use of a lastModified attribute that we introduced to the schema of deletion jobs. We look for jobs which haven’t been updated for a while, and their statuses are not “complete”. This way, we cover all of the deletion jobs that may have failed for caught and uncaught reasons.

There were other potential problems that we needed to address as well. For example, in our event-driven setup, we don’t have exactly-once delivery guarantees. This means that consumers should be expected to consume the same event more than once. Keeping track of deletion jobs here helped us, as we were able to figure out upon consuming an event whether or not we already have a job for a given bot that is already in progress.n which case, it’s safe to simply acknowledge the event and consider it a no-op.

Additionally, we needed to account for how the acknowledgement mechanism works for the Pub/Sub system. The system can consider an event unacknowledged if it wasn’t acknowledged by a consumer within a specific time window. This meant that it was important for us to acknowledge the event before actually starting the deletion, because if we waited, and we happened to be deleting quite a few data, then the system may consider it an unacknowledged event and consequently re-emit it. In this case, we needed to at least make sure that we created a deletion job record first and then acknowledge the event, then finally start the deletion process.

Using Protobuf as an event serializer

But, what about the events themselves? This is a message-passing flow as well, which involves several parties. In the simplest form, a publisher and a consumer, so what is required?

- We need a defined schema that acts as a contract between the publisher and the consumer. We don’t want the mess of not knowing what fields are there, and what types they have on top of that.

- We need this schema to be backwards compatible. We need to be able to have new consumers that can handle old events, which is a likely case to happen (e.g. during deployments, or in relatively longer cases during migrations).

- We need this schema to be forwards compatible. If we update the publishers, we need to make sure that we don’t break the already running consumers. If they consume new events, they should be able to handle the new or updated fields (e.g. having the ability to ignore them without breaking).

- Clearly, we need this backwards and forwards compatibility to be decoupled from both the publishers and the consumers. Meaning, we should be able to scale/manage either independently.

For these reasons, we decided to use Protobuf as our event serializer. We still had to be careful with how it works in order to serve the backwards and forwards compatibility features, but this is beyond the scope of this post. You can read more about Protobuf here.

message BotDeletionSubject {

string event_id = 1;

google.protobuf.Timestamp timestamp = 2;

int32 version = 3;

string bot_id = 4;

enum EventType {

EVENT_TYPE_UNSPECIFIED = 0;

EVENT_TYPE_REQUEST_PLACED = 1;

}

EventType event_type = 5;

oneof event {

RequestPlaced request_placed = 10;

}

message RequestPlaced {

google.protobuf.Timestamp placed_at = 1;

}

}

Summary

We were able to design a solution for withstanding a long running process in our architecture by introducing an event-driven system that decouples the placement of the request from the actual processing.

We were also able to add some fault tolerance capabilities owing to the retry-ability we get from a Pub/Sub system.

Our design also took recovery from failures into account, and we were able to design flows that help us recover failed jobs that can happen for several reasons, whether our application was able to catch them or not.

We made use of a serializer like Protobuf in order to enforce a schema between the publishers and the consumers. Using that, we were also able to decouple the scaling of publishers and consumers and allow that to happen independently, owing to the backwards and forwards compatibility features that Protobuf gives us.